My book Voyage of the Cormorant (Patagonia Books, 2012) takes in the major themes of my writing life: people, places, and the sea. I trace the way these forces shape and inform one another in the book, and in the features I write for The Surfer’s Journal, as well as in the continuing volume I am writing, A Following Sea. In commercial work, I seek brands that have integrity, representing their products through authentic experiences with skilled photographers/filmers and athletes. My readings for Voyage have a spoken-word element, and I enjoy engaging audiences with adventure stories.

Explore Writing: Voyage of the Cormorant | Spirit Level | Features | Contact

[scroll down for more]

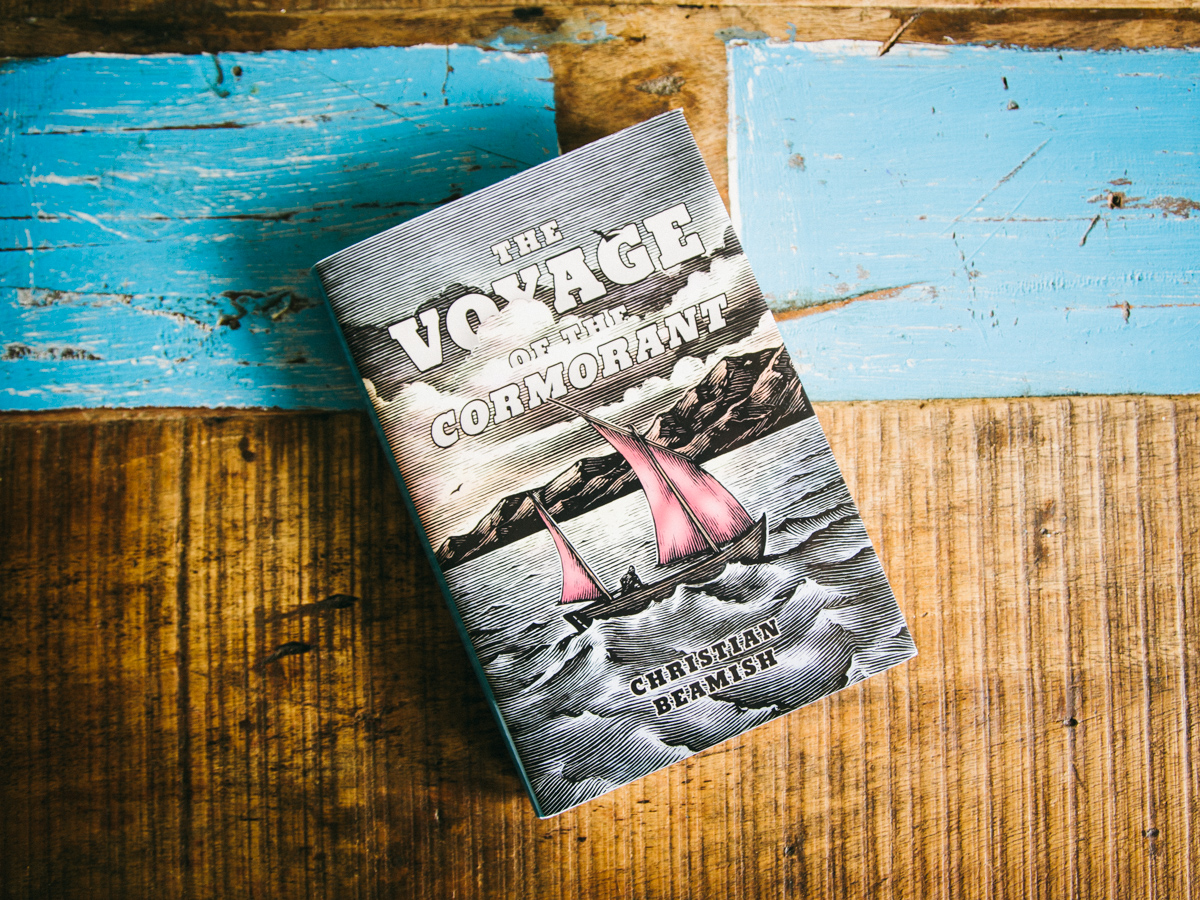

The Voyage of the Cormorant

Patagonia Books 2012

Christian Beamish built a boat in his garage and set off to find surf along the coast of Baja. He tells of his adventures in Patagonia's The Voyage of the Cormorant and the reader finds out what happens when vision meets reality.

Preview the book below:

Forward to the softcover edition:

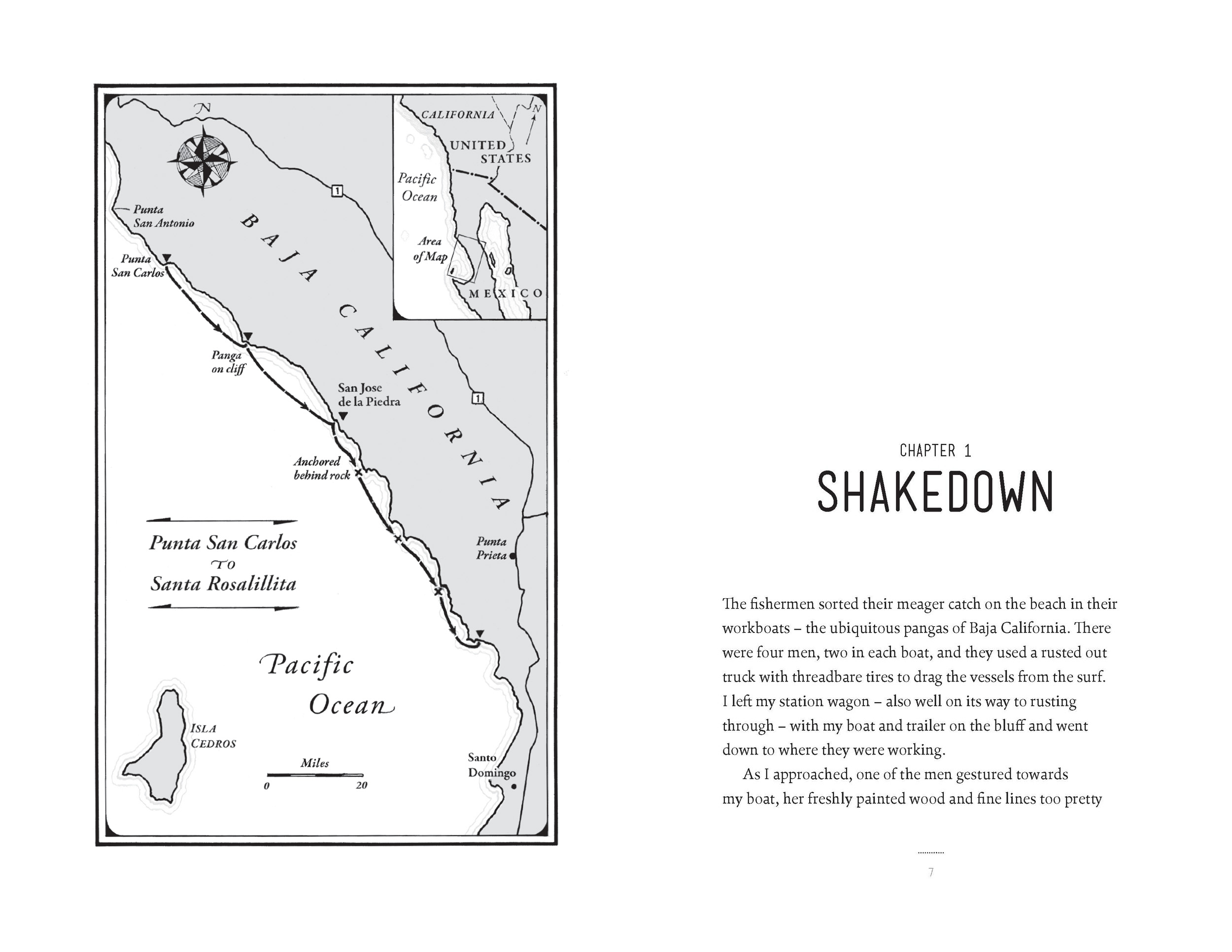

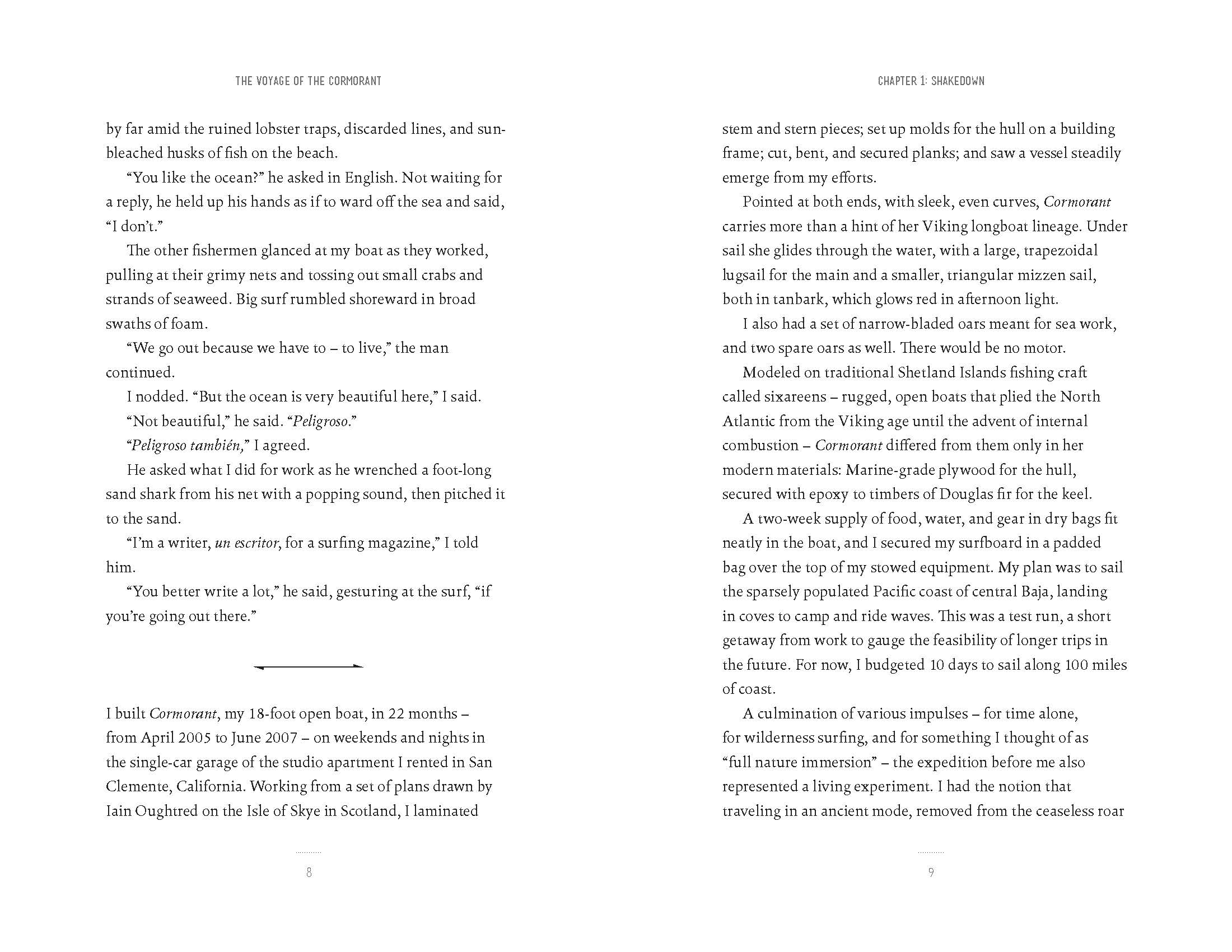

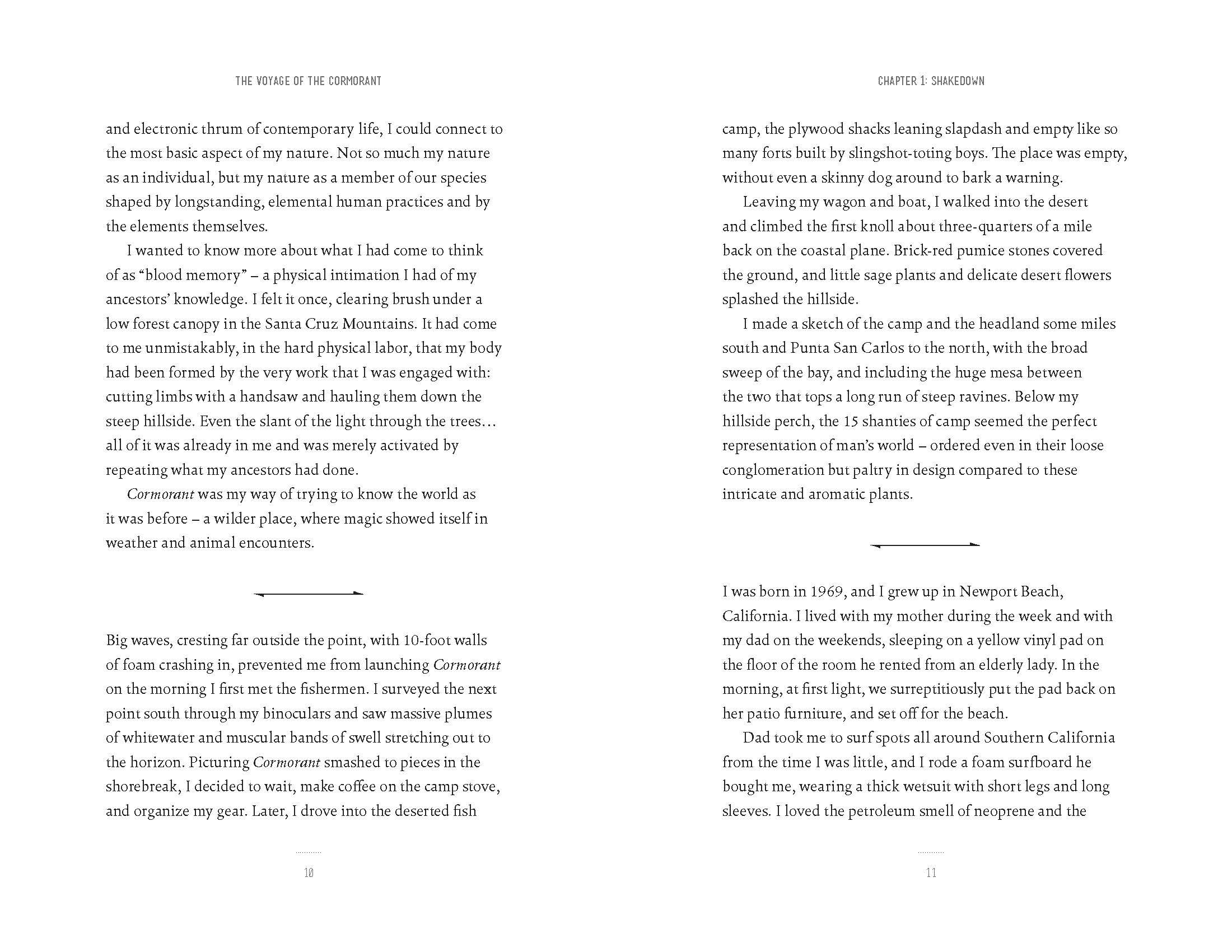

I wrote Voyage of the Cormorant in three months sitting at my desk each day in San Clemente in the cottage I rented after I’d returned from Baja and an ill-fated sail on Vancouver Island. Of course, if you consider the two years I spent building Cormorantand the two years I spent learning to sail her—as well as the years surfing from childhood on and all my dreams about this mode of voyaging—then the book took considerably longer than three months to write. Not that it matters much how long it took anyway, but there was a quality of readiness to the undertaking. The ingredients were well-prepared, and the “baking” was a final, almost incidental step in the overall process. The six-weeks I spent at The Banff Center’s Wilderness Writer’s Residency were essential also, and I am grateful for the opportunity to have had that studio in the forest in Alberta, and to have discovered for certain that given the un-interrupted time, with all food and requirements for shelter accounted for, that I could work for twelve or fourteen hours at a go—indeed, that I was greedy for the time to sit with the words and puzzle out the story. Those six weeks provided me with the first chapter.

Writing is not like sailing, except that it requires long hours of sitting. I suppose there are metaphorical similarities in the aspects of navigation, but writing is about choices of what to include, how much or how little to say about a given topic, whereas sailing, once one has left the shore for the open sea, is about dealing with the conditions at hand. I’ve received a fair amount of correspondence from people who have read Voyage, and virtually all of it has been positive, some of it very moving in the way my experience has touched someone else, made them rethink their situation—particularly how the disease of depression warps one’s view of the world and what is possible. For that I am humbled and have learned that what we say, especially in print, can have a real impact.

A question some readers have had is what I meant when I wrote about my experiences with God on my solo journey down the desert shore. That’s a tough one to nail down in a tidy declaration, and if someone were to ask me what kind of religion I have I’d say not much, but that I am a Christian, and I believe that Jesus walked on the Sea of Galilee, fed the multitudes with a couple of loaves and some fishes, turned water into wine, rolled the stone away and joined his Father in heaven. And that all of that is wrapped up with the holiness that people everywhere in the world have always known is real, regardless of the faith they proclaim. My experience of God was one of wonder at creation. As the Psalmist wrote: “They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; These see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.”

I was back down in Baja two winters ago, down in the remote corners surfing again with a couple of buddies a few months before my wife had our second child. The track winds fifty miles across the desert, and when you make the bend that finally brings the ocean into view your eyes just drink up the blue and the sparkle of it, quenching a thirst you didn’t realize was so strong. But what hit me on the trip, six years after sailing that same coast in my little craft, was the vastness of the territory and the possibility of disappearing in it whether on land or sea. Everything changes when you come back, and I surveyed that view with new eyes that marveled at my earlier motivations—how strong my desire was then for solitude, how strong it is now for my family.

My wife Natasha and I are on the most common and arduous of expeditions, raising our five-year-old Josephine and her 18-month-old brother Miles while holding to some semblance of a life in nature and surfing. Digital screens play a bigger role in our home than I am comfortable with, but we snuggled down last night and watched E.T. with Josephine and that was pretty fun so perhaps it’s the extent to which I am so comfortable with screens that concerns me. It’s nothing a few days out at the islands wouldn’t fix, sleeping under the canvas again, making that crossing in the old way, under the press of sail alone. I like the idea of a free-range family life—entire seasons in Baja, weeks and weeks on the boat combing the shore, wilderness immersion. But we have to make a living, even if our shelter for the past four years has been a modest 450-square-foot house. And we want Josephine to go to school, which she does, swinging on the monkey bars with the best of them, so the wilderness shores await. Living in Carpinteria, California is a long way from the concrete jungle as well, so we bide our time with Sundays on the quiet beach out front, or some wave riding over at the Rincon when time allows.

This house we rent, tiny as it is, wedged between the front house and the back gate, has two patches of soil on either side of the front walkway and lies not 200 steps from the salt marsh and estuary on the West end of town. It takes a few minutes to walk to the ocean, and from the threshold at the front door I can see the ridgeline of Santa Cruz Island across the channel. Natasha, daughter of a cinematographer father and an artistic/entrepreneurial/punk-rock mother in Hollywood, comes from a long line of gardeners reaching back in time to Hungary and Armenia, and she transformed those two humble patches of soil and made them a moving palette of vegetables and flowers, set off by trees in wood boxes, more plants and flowers in Talavera pots near the front door, and even a lily pond with fish and taro growing in another big glazed pot by the fence. In short, she has made this shoebox a home. She conceived, gestated, and birthed Miles here too, just as she did with Josephine in the house in San Clemente where I wrote Voyage of the Cormorant.

So indeed I have embarked on a new voyage since my little experiment aboard Cormorant. And I still have the boat, which sits on her trailer at the end of my street at my neighbor’s place, ready to launch right off the beach. We had a magical sail two months ago before the surf season started, shoving off through the gentle wavelets and heading out to the reef at the top of the point here in town. The water was exceptionally clear, the kelp forest swaying like trees on land, Josephine and Miles in their lifejackets clutching the gunwhales and peering down as we ghosted across under oars as if flying. Natasha said she had never seen Garibaldi, the thick golden-colored fish that are the State fish of California, and as if on cue, just as we met a rise in the reef where a rock ledge provides cover, three of them swam in lazy circles below us. Josephine wanted to put her wetsuit on and snorkel the reef, so we did that together and I gave her her first lesson in the art of the kelp tie to keep the boat from drifting off. The lightest of breezes came when we pulled ourselves back on board, and I put the sails up, steering with an oar to avoid tangling the rudder in the kelp, and we glided in, home in time for lunch.

This little boat Cormorant, 18-feet of Shetland Island curves and Norse-boat lineage, has been a vehicle of dreams. And this book, Voyage of the Cormorant, but one installment in an ongoing story of ocean involvement. But I love this story—the people I’ve met, the wildness I’ve encountered—and the book stands as a piece all on its own I think too. I’ve drawn up plans for a 27-footer based on what I’ve learned about simplicity and the utility of traditional designs. I’d thought to have had this boat built by now, but anyone playing the child-rearing, career-tending game will understand that the time has not been right. Still, I’ve laid out a building frame and the molds for the 27-footer, and also bent the inner stem for the bow, so I have begun. More work needs to be put into getting the bottom curve right, and there is the question of funding, but I envision Josephine and Miles helping me in the years ahead. Then again, children and power tools are probably not the best combination. All’s well though, because if I’ve learned anything from these voyaging days it’s that we get just what we need—in time.

Christian Beamish

December 29th, 2016

Carpinteria, California

Features

Steeped in the Brew (The Surfers Journal) Click here to read.

Soundings V (The Surfers Journal) Click here to read.

Soundings: Acute Angles (The Surfers Journal) Click here to read.

Gaffey Road (The Surfers Journal) Click here to read.

Soundings IV with George Greenough (The Surfers Journal) Click here to read.

The Lens: Meditations From a Distant Shore (The Surfers Journal) Click here to read.